Remy Francisco, October 25, 2024

At 63 years old, Sonny Trujillo stands upon a collapsed prison surveillance tower. He paces five steps forward, turns around, and retraces his path. For nearly 39 years, Trujillo trudged these exact steps, back and forth, in an eight by 10-foot cell within the Pelican Bay State Prison until his release in May of 2024.

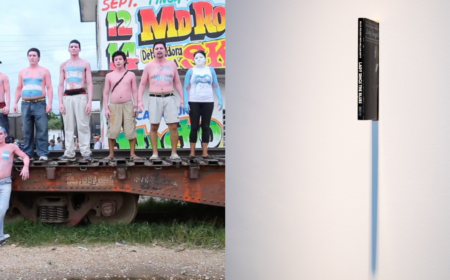

After his release, Trujillo met his now mentor Caleb Duarte, a professor of sculpture at Fresno City College and the co-founder of En Donde Era La ONU, an art collective in Chiapas, Mexico, which translates to Where the United Nations Used to Be. Together, the two launched the art installation Tres Terrenos at the UC Santa Cruz Institute of Arts and Sciences’ (IAS) October First Friday Party. The event showcases artwork exclusively from current or formerly incarcerated artists.

“We talk about prison reform, abolition and changing the way life is,” Trujillo said. “Prisons aren’t doing anything but taking all the resources from the communities, sucking all that into the industry, and it’s not doing anything except creating more sophisticated criminals and forcing people to become something they’re not — just to survive.”

The Tres Terrenos installation, or “Three Lands,” is a striking 13-foot tall scale model of a prison surveillance tower collapsed on its side. Co-created by Santa Cruz Barrios Unidos, Tres Terrenos consists solely of handmade concrete walls, compressed dirt, and wood planks. It is an extension of Duarte’s ongoing project at three different venues of the Seeing Through Stone exhibition, in which he has installed two additional models of the same dismantled tower.

With Duarte’s guidance and collaboration, Trujillo performed a vulnerable reenactment of the psychological torment he experienced during his incarceration. His is one of many stories that would have otherwise remained untold without the support of the IAS and Santa Cruz Barrios Unidos.

Duarte and Trujillo choose to collaborate with people like Daniel ‘Nane’ Alejandrez, founder of Santa Cruz Barrios Unidos because the organization works closely with local youth, current and formerly incarcerated individuals, and artists of all backgrounds.

“[The exhibition] touches on prisons, justice, and freedoms on an international scale,” said IAS staff member and fourth-year UCSC student Aiko-Bliss Ponce. “Once again we’re reminded of how all these violences are interconnected.”

The exact dimensions and materials of Trujillo’s cell. Drawn by Trujillo.

On the night of the First Friday event, The IAS exhibit cultivated a space for locals of all walks of life, young and old alike, to embrace new perspectives. Attendees sat in the audience to enjoy the live performances, explored the various works of art along the walls of the gallery, and gathered in community around the messages of Duarte, Trujillo, and other participating artists.

“It becomes a constant engagement, like an altar. The object is not just there — but the altar is always engaging with people, it’s changing, it’s evolving,” Duarte said in reference to the tower. “All of the paintings have a story to them, from Sonny’s tattoos, to Frank’s drawings in solitary confinement, to some images that we found in the office of Barrios Unidos that were mailed to them from incarcerated folks.”

Although Trujillo did not always take art seriously in his youth, he finds that his identity as a Chicano and his upbringing in the Central Valley shaped his artistry as an adult. Trujillo was the eldest of 10 children, and his mother, a single parent, moved frequently from home to home.

“I always gravitated to what it was like when I was out there in the early ’70s, the low riding scenes, [the] lowriders,” said Trujillo, referencing the celebrations of Chicano culture and modified car shows. “I did a lot of those drawings for myself, but also things that I would see that were challenging, like Native American art … that would keep my mind going and improving.”

Drawn by Trujillo.

He was often asked by friends and family to draw self-portraits, characters, and more. Art was a way for Trujillo to share his life and culture with others — a gateway to connect with the outside world and his loved ones from inside the walls of the Pelican Bay State Prison.

“I did [make art] in the early years for my daughters as they grew up, even on birthdays. If I did a card for one of my daughters on her birthday, I did a card for all of them. I didn’t want them getting jealous,” Trujillo said. “And then, little by little, gradually people fell off and we would lose contact and I would go years and years without hearing from anybody.”

From his writing in “A Voice From Within,” a letter to the youth of Santa Cruz Barrios Unidos that he wrote during his incarceration, Trujillo reveals what sustained his spirit during the 39 years he spent in prison.

“One learns to look within themselves for the strength and means needed to survive and push forward. Reaching out to assist and support others in need whenever possible. In turn helps me by giving me a sense of purpose and that all these years locked away ere not a complete waste,” Trujillo wrote. “If our art can capture and hold some ones attention for only moments maybe then they will be able to hear our voice. ”

The Seeing Through Stone exhibition is currently open and being showcased at The Institute of Arts and Sciences (IAS) in Santa Cruz from April 12, 2024 to Jan. 5, 2025. The IAS is open from 12-5 p.m. Daily (closed on Mondays) and is located at 100 Panetta Avenue, Santa Cruz.

Read article on City on a Hill Press.

Top photo by Heather Tran.