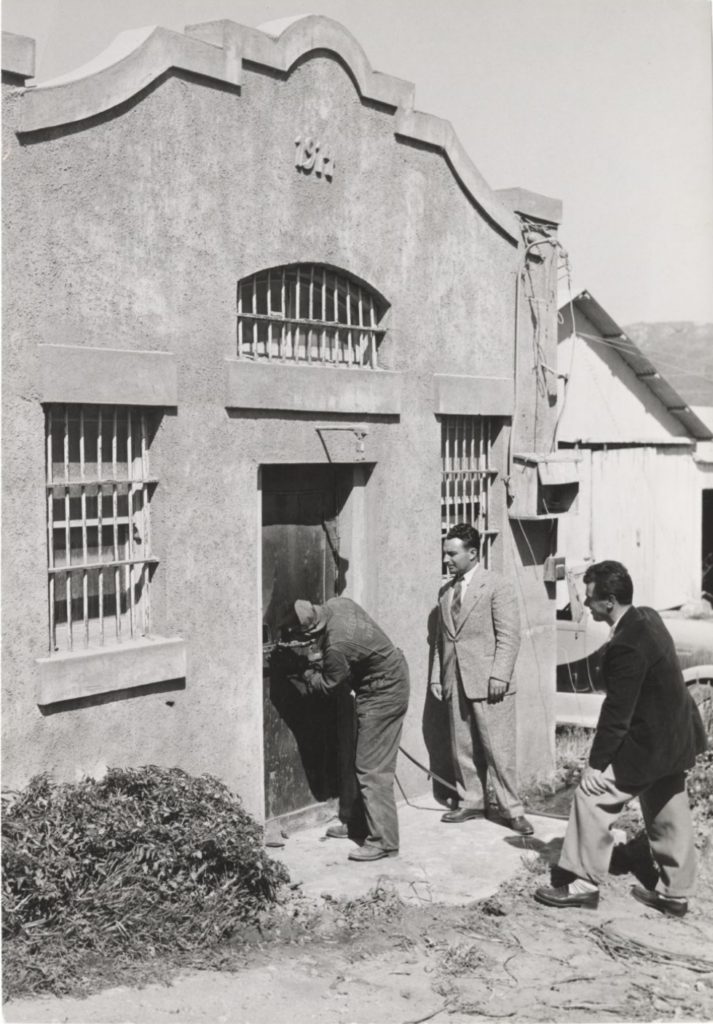

From September 2022 to June 2023, The Writing on the Wall is on view at the Davenport Jail. A collaborative and immersive artwork by artist Hank Willis Thomas and scholar and activist Dr. Baz Dreisinger, the installation covers the walls, ceilings, and floors of the two-room county jailhouse with writings by individuals in prisons around the world. Letters, drawings, and poems plaster the jail’s stark cement surfaces, supplementing the history of a punitive space with the words and images produced by people behind bars.

The Davenport Jail provides regional context for the larger tragedy of incarceration evocatively layered onto its walls. It serves as a reminder, as this essay addresses, that even small jails and prisons have important things to tell us about larger structural forces that have brought about a global crisis of incarceration. The jail at Davenport exemplifies a common historical phenomenon: the construction, all across the United States, of carceral spaces alongside new rural agricultural and industrial concerns during the early twentieth century. It demonstrates just how thoroughly issues of labor, land use, and race were already connected at the site of the prison even before the mighty prison-building boom that transformed California’s penal landscape after the 1970s.

History of the Davenport Jail

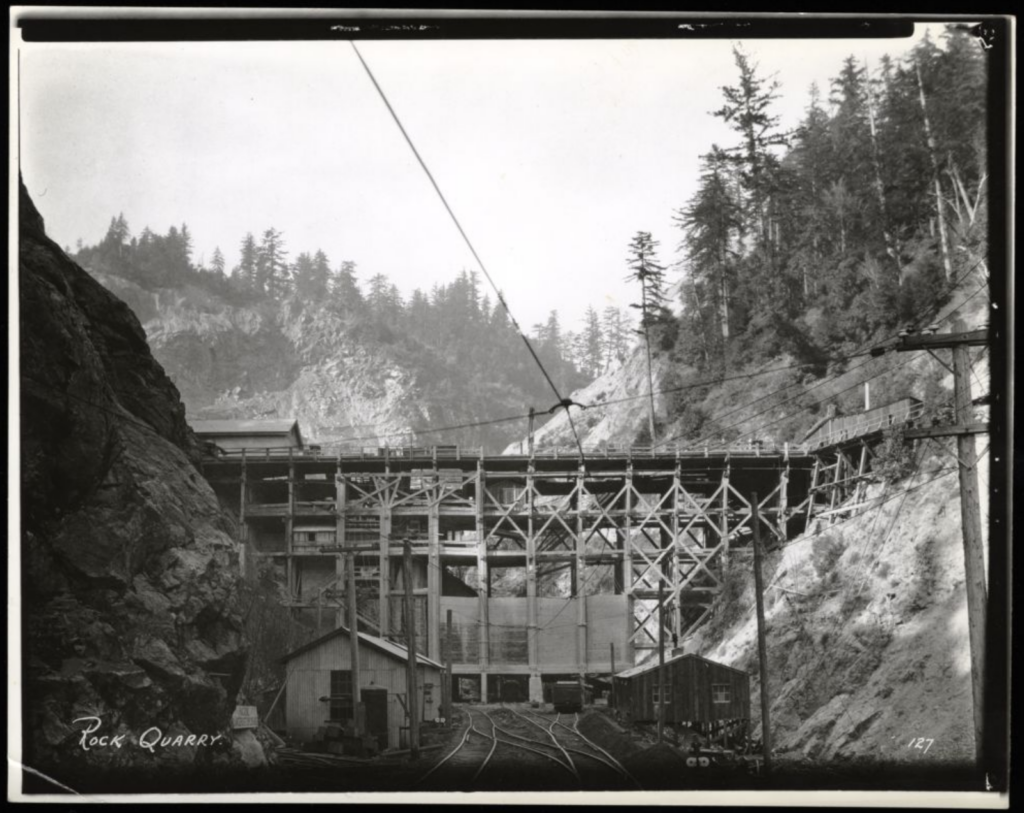

The small community of Davenport was transformed by the Santa Cruz Portland Cement Company’s construction of a massive cement plant in 1905.1 Cement from here would help to rebuild San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake and even end up in the Panama Canal. Davenport became a company town, many of its services provided by the cement plant that also dominated its civic life, and in 1913 work began on a jail for the town.2 The jail’s story is bound up with the history of the cement company, which deeded land and offered materials for its construction. By 1933 the jail was even overseen by an employee of the cement plant.3

Labor

Labor was the largest single cost that went into making cement. In 1929, the Santa Cruz Portland Cement Company estimated that it cost 65 cents to produce a single barrel of their product; of this amount, 22 cents went to paying labor.

Controlling labor costs meant suppressing unionization efforts. Jails and prisons were used to punish activists and to tamp down attempts made by workers to improve their conditions. During the Salinas lettuce strike of 1934, for example, labor organizers were arrested by the police then charged with vagrancy.4 Jails were also potential sources of labor, much as some state industries today rely on incarcerated workers to produce furniture, clothing, and other goods. When workers attempted to unionize cement plants in Texas in the 1930s, the legislature recommended setting up state-run alternatives staffed exclusively with convict labor.5 In October 1937, the Santa Cruz County Board of Supervisors adopted a resolution permitting the use of jailhouse labor to maintain public buildings like the courthouse.6

During the period when the Davenport Jail was operational, Santa Cruz County saw repeated acts of racial violence against non-white workers. A five-day riot aimed at Filipino laborers gripped Watsonville in 1930, claiming the life of Fermin Tobera. Further inland, police forces helped direct the violence; in 1929, the local police chief led a vigilante group in Exeter that dispersed Filipino labor camps and burned the property of farmers who employed Filipino workers.7 Images and eyewitness reports preserve a terrifying history of lynching in Santa Cruz, including a case in the 1870s when a mob forcibly took two men of Mexican and Ohlone descent from the local jail and hung them on the Water Street Bridge. A photograph of the event, which we deliberately choose not to reproduce here, attests the chilling mechanisms by which the town’s white population enforced their position atop a social and economic hierarchy.

The Davenport Jail played a role in these overlapping histories of labor and race. A story in the Santa Cruz Evening News from 1918 headlined “Mexican in Jail: He Couldn’t Show Necessary Card” reports that one of the many Mexican workers who journeyed to Davenport in search of employment at the cement plant was thrown in jail for not producing the right paperwork. The article’s author drew a connection between the plant’s products and the building’s material, writing that the worker “is studying the cement formations in the county jail instead of assisting in the manufacture of the article.”8

Across the country, industrial foundations like cement plants commissioned jails to accompany the settlements that grew up with them. In Missouri, the Atlas Portland Cement Company dominated the small labor camp-turned- town of Ilasco. Here, too, the company provided the materials for the construction of a small jail described by the local newspaper in 1909 as “a sweat box. It has four cells and is as dark as any night.”9 A forbidding building, it signals its punitive function through its bleak appearance. Remarkably, the Ilasco jail also ended service in 1935, about the same time as its Davenport counterpart.

Environmental Consequences

Although the health hazards of working in cement plants were much debated in the early twentieth century, it was obvious to all that the industry devastated the local environment. The violent process of extracting the raw materials that would be turned into cement wreaked havoc on the surrounding landscapes, and the plants themselves ran on polluting process that released large volumes of dust, fumes, and smoke into the atmosphere. “When the children went to school there was dust on the side- walks, so therefore they left their footprints,” recalled a Davenport resident. A 1912 article published in The Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, noting the damage done to local crops by Portland cement works in Riverside and Colton in southern California, concluded that “the question of the proper relationships which should exist between the factory and the surrounding inhabitants has become a very important social problem.”10

Prisons, Ruth Wilson Gilmore argues, are “new forms of environmental racism which are equally, if differently, destructive of the places prisoners come from and the places where prisons are built.”11 The small Davenport Jail might not seem to have generated much waste or consumed many resources, as large prisons do in California today. But both the Davenport and Ilasco buildings are airless, unsanitary buildings that were constructed without the health of their inhabitants in mind; in this way, they signal how bigger prisons contain people in warehouses that actively damage their physical and mental wellbeing. And they were vital pieces in a civic network geared towards sustaining an ecologically unsound, extractive industry.

The Davenport Jail’s Legacy

The Davenport Jail ceased operations in the 1930s. A large new county jail was built in Santa Cruz in 1937 to replace the smaller institutions that dotted the county. Less than forty years after its construction, the new jail would be ranked as one of the five worst in California by the State Board of Corrections.12

Over time, a myth has grown up that the Davenport Jail was used only twice. This erroneous fact was even cited in the 1991 application to have the building placed on the National Register of Historic Places. In addition to the cases already mentioned, however, historic newspaper reports show that the jail was used to incarcerate all sorts of people; in November 1927, for example, a local artichoke grower was jailed there on a reckless driving charge before being transported to Santa Cruz the next morning to stand trial.13 What does it mean to present a jail or a prison as rarely used? Or as the occasion for ghost tales, funny stories, or titillating anecdotes, as prison museums and true crime media often do today?

The erasure of this jail’s history helps to frame a picture of Davenport as a quiet, law-abiding town, untouched by the forces of racism, labor unrest, and industrial exploitation that would combine to lay the grounds for the explosion of mass incarceration in the later twentieth century. But the tone of how prisons are represented and their histories told is also important. A newspaper article in 1932 jokingly compared the jail to an unpopular resort hotel: “no applications have come in for residence nor has it been necessary to invite any patrons for over a year and a half,” ran the story.14 The prison was already made to look cute in a way that makes its punishing, threatening functions disappear. As critic Sianne Ngai puts it, “cute objects have no edge to speak of.”15 The work of Hank Willis Thomas and Dr. Dreisinger teaches us to see that no prison is, in fact, cute; and that even the smallest institutions of punishment are made of sharp edges.

Notes

1 Robert Whitman Lesley, History of the Portland Cement Industry in the United States: With Appendices Covering Progress of the Industry by Years and an Outline of the Organization and Activities of the Portland Cement Association (Chicago: International Trade Press, 1924), 298.

2 Santa Cruz Evening News, vol. 12, no. 133 (October 7, 1913).

3 Santa Cruz Evening News, vol. 51, no. 48 (January 25, 1933).

4 Howard A. DeWitt, “The Filipino Labor Union: The Salinas Lettuce Strike of 1934,” Amerasia Journal 5, no. 2 (1978), 12.

5 Gregg Andrews, “Unionizing the Trinity Portland Cement Company in Dallas, Texas, 1934-1939,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly 111, no. 1 (2007), 46.

6 Santa Cruz County Documents Collection, MS 301, Box 13, University of California, Santa Cruz, McHenry Library Special Collections.

7 Howard A. De Witt, “The Watsonville Anti-Filipino Riot of 1930: A Case Study of the Great Depression and Ethnic Conflict in California,” Southern California Quarterly 61, no. 3 (1979), 294.

8 Santa Cruz Evening News, vol. 22, no. 58 (July 10, 1918).

9 Gregg Andrews, City of Dust: A Cement Company in the Land of Tom Sawyer (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1996), 54.

10 Walter A. Schmidt, “Control of Dust in Portland Cement Manufacture by the Cottrell Precipitation Processes,” The Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 4, no. 10 (1912), 719.

11 Ruth Wilson Gilmore, “Scholar Activists in the Mix [2005],” in Abolition Geography, eds. Brenna Bhandar and Alberto Toscano (New York: Verso, 2022), 93.

12 Joe Luttner, Peter Miller, and Sharman Murphy, “Resisting the Police- Industrial Complex in Santa Cruz,” Crime and Social Justice, no. 2 (1974), 58.

13 Santa Cruz Evening News, vol. 41, no. 19 (November 22, 1927). He was fined $100.

14 Santa Cruz Evening News, vol. 50, no. 75 (August 27, 1932).

15 Sianne Ngai, “The Cuteness of the Avant-Garde” Critical Inquiry 31, no. 4 (2005), 814.