June 24, 2024

Years ago, I visited a dairy farm in Wisconsin where someone left a gate open. I’ll never forget the sight of the first cow to run off—the massive beast kicked up its heels and scampered away, relishing its new-found freedom. On a far more serious note, Seeing Through Stone, a three-institution group show in San Jose and Santa Cruz, takes on the ramifications of the prison industrial complex and the devastation that walled confinement wreaks on the psyche. Incarcerated or formerly incarcerated artists, as well as activists in the abolition movement – 81 in all, including several collectives — argue that prisons are, in essence, an extension of slavery, an institution in which racism and class conflict manifest in brick and mortar.

The title comes from a poem by Etheridge Knight, who, in 1968, wrote of “seeing through stone” while incarcerated at Indiana State Prison. The curators offer a similar vision: a world where “people seek safety with, rather than from, each other.”

The exhibition — a collaboration between the San Jose Museum of Art, the Institute of Arts and Sciences at UC Santa Cruz, and Santa Cruz Barrios Unidos, a community-based cultural and civil rights organization — reflects the struggle among arts institutions to respond to calls for enhanced equity and inclusion. Barrios Unidos, a set of converted storefronts accessed by a different audience than a museum might attract, is a case in point. Many of the works on view deal with the reality of imprisonment and its impact on individuals and families—often incorporating primary documents like interviews and letters from inmates.

Several works appear at two of the three sites, creating an echo effect that knits the three exhibitions together. For example, I missed the video And Water Brings Tomorrow by Ashley Hunt amid all the tumult at the San Jose Museum of Art. But at Barrios Unidos, it grabbed my attention. The piece consists of interviews with former convicts as they tour long-closed prisons. Now elderly, they emanate an uncanny humility as they speak, sadly but without bitterness, as when one relates how “…[an old friend] got out in January on humanitarian grounds,” only to die of cancer in June. A painting by Nathaniel McCray, consisting of a few strokes on a powder-blue square, shows a Black boy at play. The handwritten (heart-rending) title: MY SON. Two prints on handkerchiefs recall the great Latino graphic art of the 1960s. In one, a woodblock print of a wire cutter bears the slogans “no fence uncut” and “no one is illegal.” In the other, a red ladder on a white ground says, “No wall unclimbed.” They’re the work of Frank Alejandrez and Javier Haro.

Several pieces at the San Jose Museum stand out for their ephemeral and poetic approach to this fraught subject. Tea Project collaborators Amber Ginsburg and Aaron Hughes, working with former Guantanamo prisoners (Ghaleb Al-Bihani, Khalid Qasim, and Moath al-Alwi) created Ode to the Sea, a large sail-shaped canvas object made of tea-stained U.S. army uniforms. It evokes that compound’s seaside location and the dream of floating away. A realistic prison-made replica of an 18th-century sailing ship by al-Alwi, fashioned

from scrounged objects, reiterates the idea of isolation and transcendence. Spanish artists Patricia Gómez and María Jesús González’s stunning mural-scale reproductions of walls from detention centers, A tous les clandestins, also shows the angst and anger recorded by people marking time. The artists employed a technique that allowed them to chemically transfer graffiti from prison walls onto black canvas to create exact replicas. The results bring to mind distressed Rothkos laced with text portions resembling those seen in the paintings of Raymond Saunders and Squeak Carnwath. (An even larger example of their work is on view in the UC Santa Cruz venue.)

An installation by Charles Gaines, Sky Box II, mounted in a light-controlled room, is the most memorable piece in the exhibition. It’s a wall covered floor-to-ceiling with framed reproductions of original handwritten legal papers from the infamous Dred Scott decision, the Supreme Court case that confirmed the right of slaveholders to recover their “property” anywhere in the United States. The harsh light illuminating it dims to complete darkness every ten minutes or so, magically transforming what we see into a convincing recreation of the Milky Way. When I visited, a group of children broke into applause. The harsh and coercive Scott legalese, when superseded by the vastness of outer space, delivers a profound and transcendent experience.

Several other pieces in the San Jose deliver subtle surprises. Lac Seul First Nation Canadian artist Rebecca Belmore’s At Pelican Falls recapitulates an event pictured in a 1955 found photograph taken by John McFie at an Indian school in Canada at which Indigenous children were separated from their families and forbidden to acknowledge their heritage or speak their native languages. It does so first in a video and again in an installation. The original image shows several boys in blue denim school uniforms observing someone swimming from a vantage point on shore. In the video, the swimmer wades up to his waist and disappears. The installation consists of the uniforms pooled on the floor to stand in for the lake, with a pile of the same material representing the wading figure. Together, they manifest a sense of cumulative history, suffering and cultural eradication.

Diptychs by Sofia Karim, a British architect, is a grid of six pairs of images projected onto empty pages, showing the ways architectural space affects human feelings of safety or anxiety in prisons. (Each paired projection is divided between image and text.) Maria Gaspar’s Invisible Things Are Not Necessarily Not-There (after T.M.)are mysterious small glass objects that turn out to be casts of smashed bars and bricks from a demolished jail.

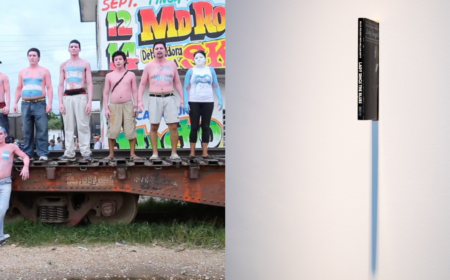

The sprawling installation at the UC Santa Cruz Institute of the Arts and Sciences also has standout work, though it would have benefitted from some pruning as many of the works intrude upon each other’s space. More than once, I thought I’d stumbled into a storage space rather than part of the exhibition. That said, an immersive video installation, Ancestral Intelligence by the Brazilian group Frente 3 de Fevereiro, particularly affected me. It’s a claustrophobic prison-cell-sized chamber with floor-to-ceiling video projections on three sides showing scenes of political strife in the streets, a mix of violence, hope, optimism and anger visible in the faces of the demonstrators. It haunted me all day.

Carlos Motta, in his Capuchin Order, and Sofia Karim (again), in Memories of Keraniganj Jail, create seductively attractive architectural models—she with 3D prints of prison conditions in Bangladesh, he with buildings implicated in the slave trade in his native Colombia. Gabriela Mureb’s Machine #4: Stone (Crank), a drill mounted on a pedestal, perpetually bores into a chunk of marble, evoking the Sisyphus-like labor of getting through a day, incarcerated or otherwise.

Large theme shows like this tend to develop “mission drift,” in which the premise becomes diluted by tangential works that attempt to illustrate the curatorial argument without actually embodying it. Seeing Through Stone works best when it addresses the carceral state, showing that prisons are part of a system of social control that builds literal or figurative walls between people, whether gated communities or blockaded national borders. At a time when a presidential candidate promises to litter the American landscape with concentration camps and when the US continues to be the world’s leading jailer, Seeing Through Stone delivers important messages about what it means to lock people up en masse.

# # #

“Seeing through Stone” @ the San José Museum of Art, the Institute of the Arts and Sciences at UC Santa Cruz and Santa Cruz Barrios Unidos through January 5, 2025.

Read full article on SQUARECYLINDER.com.